Introduction

Diabetes is a demanding chronic disease for both individuals and their families (1). Diabetes is characterized by elevated glucose in the blood. Type 1 diabetes refers to the fact that the pancreas produces no insulin whereas type 2 diabetes refers to the case where the pancreas produces an insufficient amount of insulin. Research has demonstrated a relationship between diabetes and various mental health issues, which include psychiatric disorders and other problems that are specific to people living with diabetes (2). There are some terms that are used to characterize the mental health problem associated with diabetes. For instance, “diabetes distress” refers to the negative emotions and burden of self-management in people with diabetes, which is used to describe “the despondency and emotional turmoil specifically related to living with diabetes, in particular the need for continual monitoring and treatment, persistent concerns about complications, and the potential erosion of personal and professional relationships (2–4). “Psychological insulin resistance” refers to the refusal or reluctance to accept insulin therapy, which can delay the start of the treatment for a period of time (5). Fear of hypoglycemia is another common concern in diabetes. Understanding the association between diabetes and mental health is important because psychiatric and diabetes-specific psychosocial issues are related to reduced participation in self-management activities that can decrease the quality of life. Moreover, psychiatric disorders in diabetes patients increase the risk of diabetes complications and early mortality (6).

Indeed, previous studies have found that diabetes is associated with major depressive disorder [e.g., (7–10)], anxiety [e.g., (11, 12)], bipolar disorders [e.g., (13, 14)], schizophrenia (15), personality disorders [e.g., (16, 17)], stress, trauma, abuse and neglect (18, 19), eating disorders (20, 21), and sleep issues [e.g., (22)]. Moreover, the associations between diabetes and mental health could be totally bi-directional [e.g., (10)]. However, these studies mostly involve small sample sizes.

Developed by Goldberg in the 1970s, the general health questionnaire (GHQ) is a reliable measure of mental health. Moreover, among other versions of GHQ, the GHQ-12 is a self-reported questionnaire that includes 12 items, each of which is assessed with a Likert scale (23). The psychometric properties of this questionnaire have been evaluated in a lot of studies (24–28). Moreover, it has been proven that the GHQ-12 has good specificity, reliability, and sensitivity (29, 30). Although the GHQ-12 was initially developed as a unidimensional scale, there are some controversies regarding if GHQ-12 should be used as a unidimensional scale or a multidimensional structure. Between two or three factor models, there is a lot of empirical support behind a three-factor model of the GHQ-12 (31–35), which include GHQ-12A (social dysfunction and anhedonia; six items), GHQ-12B (depression and anxiety; four items), and GHQ-12C (loss of confidence; two items). A typical argument made that favors the use of the unidimensional model of the GHQ-12 rather than the factor solution is that there is a high correlation between these factors. For instance, the correlation between the 3 factors varied from 0.72 to 0.84 in Padrón et al. (33), from 0.76 to 0.89 in Campbell and Knowles (32), and from 0.83 to 0.90 in Gao et al. (35). However, recent studies using simulated data has proven the imposition of a simple structure may artificially inflate correlations between modeled factors [e.g., (36)]. Thus, as suggested by Griffith and Jones (37), “taking these correlations as justification for unidimensionality risks a self-fulfilling prophecy of simplicity begetting simplicity.” Given these controversies, the current study considers both the unidimensional and multidimensional structure of the GHQ-12.

Thus, although previous studies have shed light on the associations between diabetes and various types of mental health issues with a focus on depression and anxiety, much less is known about how diabetes is associated with other dimensions of mental health such as social dysfunction and anhedonia and loss of confidence in a large nationally representative survey from the United Kingdom. The aim of the current study is to investigate how diabetes is related to general mental health and dimensions of mental health. The current study hypothesized that the GHQ-12 has three underlying factors labeled as GHQ-12A (social dysfunction and anhedonia; six items), GHQ-12B (depression and anxiety; four items), and GHQ-12C (loss of confidence; two items). Moreover, diabetes patients are expected to have worse general mental health and dimensions of mental health.

Methods

Data

This study used data from Understanding Society: the UK Household Longitudinal Study (UKHLS), which has been collecting annual information from the original sample of UK households since 1991 [when it was previously known as The British Household Panel Study (BHPS)]. This data set is publicly available at https://www.understandingsociety.ac.uk. The current study used data in Wave 1, which was collected between 2009 and 2010 (38). Participants received written informed consent before participating in the study. Age and sex-matched healthy controls were randomly selected from these participants. Among them, there were 2,255 diabetes patients with a mean age of 60.29 (SD = 14.78) years old with 53.35% males and 14,585 age and sex-matched participants with a mean age of 60.47 (SD = 10.93) years old with 53.40% males who indicated that they were not clinically diagnosed with diabetes.

Measures

Diabetes

Participants answered the question “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you have any of these conditions? Diabetes” to indicate if they have diabetes. Self-reported diabetes is a valid measure of diabetes status in various countries (39–45). However, the specific type of diabetes was not assessed in this sample.

Mental health

Mental health was measured using the GHQ-12 (23). The GHQ-12 used the Likert method of scoring ranges from 0 (“Not at all”) to 3 (“Much more than usual”). A summary score across all the 12 items was used to represent general mental health. A higher score means worse mental health. For the purpose of the factor analysis, the GHQ-12 was scored from 1 (“Not at all”) to 4 (“Much more than usual”).

Demographic controls

Demographic controls in the model include age (continuous), sex (male = 1 vs. female = 2), monthly income (continuous), highest educational qualification (college = 1 or below college = 2), legal marital status (single = 1 vs. married = 2), and residence (urban = 1 vs. rural = 2).

Analysis

Factor model

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with oblique rotation was applied to the GHQ-12 dataset on MATLAB 2018a with native MATLAB function with a pre-specified number of factors of 3. The three factors are expected to be GHQ-12A (social dysfunction and anhedonia; 6 items), GHQ-12B (depression and anxiety; 4 items), and GHQ-12C (loss of confidence; 2 items). Both the GHQ-12 summary score and factor scores are standardized (mean = 0, std = 1).

Linear model

First, a general linear model was constructed by taking demographics from participants without diabetes as predictors and GHQ-12 summary score and three-factor scores underlying the GHQ-12 as the predicted variables respectively. Second, demographic data from participants without diabetes were included in the model as predictors to forecast what GHQ-12 summary score and 3-factor scores underlying the GHQ-12 might be predicted if they have not been clinically diagnosed with diabetes. Finally, a one-sample t-test was performed to evaluate if diabetes patients had a higher or lower real GHQ-12 summary score and 3-factor scores underlying the GHQ-12 than predicted. This approach is more advantageous than paired-sample t-tests because it can control for demographic confounders.

Results

The factor analysis yielded three interpretable factors including GHQ-12A (social dysfunction and anhedonia; six items), GHQ-12B (depression and anxiety; four items), and GHQ-12C (loss of confidence; two items). The loadings of these items can be found in Table 1.

Table 1. The factor loadings for the three-factor structure of the GHQ-12.

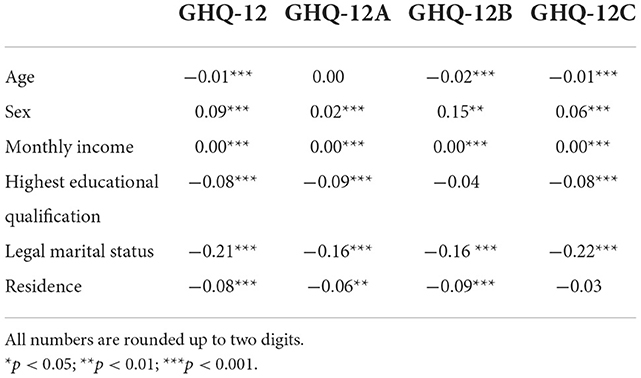

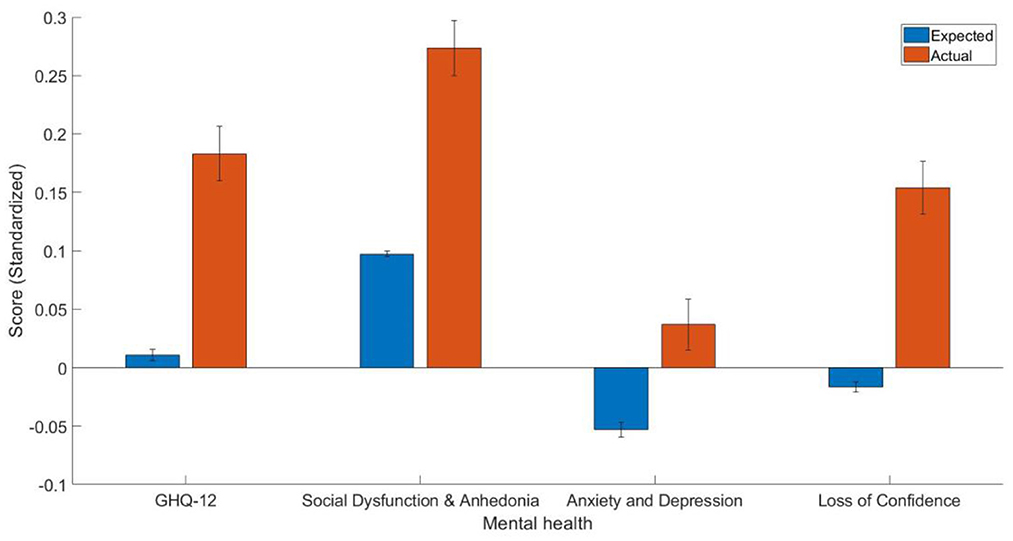

The estimate of the predictors in the generalized linear models trained on people without diabetes can be found in Table 2. The current study found that diabetes patients have worse overall mental health as indicated by the GHQ-12 summary score [t(2, 254) = 7.49, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.17, 95% CI (0.13, 0.22)], GHQ-12A [t(2, 254) = 7.46, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.18, 95% CI (0.13, 0.22)], GHQ-12B [t(2, 254) = 4.28, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.09, 95% CI (0.05, 0.13)], GHQ-12C [t(2, 254)=7.68, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.17, 95% CI (0.13, 0.21)]. The mean and standard error of predicted and actual standardized scores can be found in Figure 1.

Table 2. The estimates (b) of linear models trained based on demographic predictors.

Figure 1. The mean and standard error of the estimated GHQ-12 summary score and three-factor scores (standardized).

Discussion

The aim of the current study was to investigate how diabetes is associated with mental health in general and the dimensions of mental health. The current study predicted that diabetes patients have worse mental health in general and dimensions of mental health. Indeed, the results obtained from the train-and-test approach are consistent with the hypothesis that general mental health and dimensions of mental health are affected by diabetes.

In the current study, the factor analysis yielded 3 factors including GHQ-12A (social dysfunction and anhedonia; six items), GHQ-12B (depression and anxiety; four items), and GHQ-12C (loss of confidence; two items). The 3-factor structure solution found in the current study is largely consistent with previous studies that identified three factors in GhQ-12 (29, 42, 46). Moreover, as shown in Table 1, the factor loadings were represented to be high in the current study.

Importantly, the main findings of the current study were that diabetes patients have worse mental health than controls, which is largely consistent with the literature. Regarding the negative association between diabetes and social dysfunction and anhedonia, previous studies have found that anhedonia was associated with an increased chance of suboptimal glycemic control (HbA1c ≥ 7%) in patients with type 2 diabetes [(47), and see (48) for a review]. Diabetes patients also had depression and anxiety problems in the current study, which is largely consistent with the literature [e.g., (7, 8)]. For instance, it has been shown that clinically relevant depressive symptoms among people with diabetes are ~30% (7, 8). Moreover, clinically diagnosed diabetes but not undiagnosed diabetes was associated with a doubling of the prescriptions for antidepressants, which is consistent with the hypothesis that the associations between diabetes and depression may be attributable to factors that relate to diabetes management (49). Individuals with depression may have a 40–60% increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes (49, 50). Furthermore, the co-occurrence of depression and diabetes is worse than when each illness occurs separately (5). Depression in people with diabetes may amplify the symptom burden by a factor of around 4 (51). Depression in diabetes patients lasts longer and has a higher likelihood to reoccur compared to people without diabetes (52). Major depressive disorder is also associated with underdiagnosed in people with diabetes (53). On the other hand, anxiety is a typical comorbid with depressive symptoms (54). Grigsby et al. (11) estimated that 14% of patients with diabetes suffer from a generalized anxiety disorder. Moreover, this number doubled for patients who experience subclinical anxiety disorder and tripled for patients who had at least some anxiety symptoms (11). Anxiety disorders were also found in one-third of people with type 2 diabetes and serious mental illness and were also associated with increased depressive symptoms and decreased level of function (55). In addition, long-term anxiety is positively related to the risk of developing type 2 diabetes (12). The finding that diabetes patients experience more loss of confidence is consistent with the notion that chronic diseases including diabetes are associated with loss of confidence [e.g., (56)]. This finding implies that improving confidence in patients is important because it may lead to better outcomes (57). Moreover, the effect size as indicated by Cohen’s d is smaller for depression and anxiety may indicate that diabetes patients are more affected in other dimensions of mental health, so research in this area should not focus on anxiety and depression alone in diabetes patients.

In conclusion, the present study confirmed the three-factor solution of the GHQ-12 and applied it to a sample of participants who indicated that they had diabetes. Although there are strengths of the current study including a large sample size and a train-and-test approach that takes demographics into account, there are also some limitations. First, although participants indicated that they had diabetes, it remains unclear what types of diabetes (e.g., type 1 vs. type 2) they had. Future studies should ask about specific diabetes that patients might have and how they relate differently to mental health. Second, given the nature of the current study is cross-sectional, it remains unclear if diabetes causes people to have worse mental health or if worse mental health causes people to have diabetes. Future studies should adopt longitudinal approaches in order to establish causality. Third, the current study was largely based on self-reported measures, which could cause self-reported bias. Future studies should use a more objective assessment of diabetes and mental health. Finally, the data was quite old, which may be less informative today. Future studies should use more recent data to study such associations.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://www.understandingsociety.ac.uk.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by University of Essex. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

WK: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, resources, software, writing—original draft, and writing—review and editing.

Funding

This work was supported by the Imperial Open Access Fund.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Snoek FJ, Kersch NY, Eldrup E, Harman-Boehm I, Hermanns N, Kokoszka A, et al. Monitoring of individual needs in diabetes (MIND): baseline data from the cross-national Diabetes Attitudes, Wishes, and Needs (DAWN) MIND study. Diabetes Care. (2011) 34:601–3. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1552